Exam 4 Details

Hi everyone! Here are the details for our last exam.

Date/time. Exam 4 is scheduled for Wednesday, December 10. It will open at 12:00 am that day, and you will have until 11:59 pm on Wednesday to complete it. You’ll have 2 hours to complete it once you open it. Just be sure to submit it by 11:59 on Wednesday 12/10.

Password. The assessment password is YouarethebestD2s

Points/questions. The exam has 33 multiple-choice, one-answer questions, each worth one point.

Exam breakdown. Here’s the breakdown by lecture.

- Pituitary: 1 question

- Thyroid: 8 questions

- Adrenal: 4 questions

- MEN: 1 question

- Bone and Joint: 10 questions

- Muscle: 2 questions

- CNS: 7 questions

Please let me know if you have any questions!

NO in-person class tomorrow!

Due to an unexpected scheduling conflict, Dr. Koutlas is not able to present his lecture in the classroom live tomorrow. So I have posted a lecture recording for you to watch at your convenience. Sorry for the last minute change! Let me know if you have any questions.

Exam 3 Details

Hi everyone! Here are the details for our third exam.

Date/time. The exam will be open from 12:00 am until 11:59 pm on Wednesday, November 19th and you’ll have 2 hours to complete it once you start. Just be sure to get it uploaded by 11:59 pm Wednesday night.

Password. The assessment password is AwesomeD2s.

Points/questions. The exam has 28 multiple choice, single-answer questions and is worth a total of 28 points.

Exam breakdown. Here’s the breakdown by lecture. Some of the questions ask you to differentiate between acute leukemia, chronic leukemia, lymphoma and/or myeloma, so I had to lump those two lecture topics together.

- Anemia: 8 questions

- Acute leukemia, chronic leukemia, lymphoma and myeloma: 10 questions

- Hemostasis: 5 questions

- Bleeding and thrombotic disorders: 5 questions

Suggestions for studying. It would probably be a good idea to do Quiz 3 (even though it’s not actually due until Friday – because it will test your knowledge) and go through the Exam 3 review as part of your studying process.

As always, the exam questions will all come straight from the PowerPoint slides for each lecture. For diseases, focus on the “Things You Must Know” slides to help you narrow things down to the points I think are most important.

That’s all I can think of! Please let me know if you have any questions. I’ll be checking my email frequently tonight 🙂

Reminder: NO class tomorrow! Quiz 3 online.

Just a reminder that we will NOT have class in-person tomorrow. You guys asked if we could do an asynchronous class because you have a radiology exam right after our class – and since it’s just a quiz and an exam review, those are things that are easy to switch to online.

I posted Quiz 3 and the Exam 3 review Kahoot on our Schedule page.

Please complete quiz 3 by midnight on Friday, 11/21.

Let me know if you have any questions!

Really, please ask me some questions. I haven’t gotten any and that kinda makes me anxious. So if any little thing doesn’t make sense, drop me an email. Thanks!

Exam 2 scores posted

Scores for exam 2 are now posted on Canvas. You did great, as always – the mean was 96%!

Exam 2 Details

Hi everyone! Here are the details on exam 2. We’ll be using Examsoft as usual; there is no camera proctoring, but I trust you to take the exam without using outside materials.

Date/time. The exam will be open from 12:00 am until 11:59 pm on Monday, October 27, and you’ll have 2 hours to complete it once you start.

Password. The assessment password is Goodexam2. Because I think it is a good exam and also I hope everyone gets a good score.

Points/questions. The exam has 33 questions, each worth one point. All questions are multiple choice with one correct answer.

Exam breakdown. Here’s the breakdown by lecture:

- Upper GI: 2 questions

- Lower GI: 3 questions

- Pancreas/Liver/Gallbladder: 5 questions

- Renal: 7 questions

- Skin: 7 questions

- Female reproductive: 6 questions

- Male reproductive: 3 questions

That’s all I can think of! Please let me know if you have any questions.

How to remember nephritic vs. nephrotic syndrome

One of the things I covered in our Renal Path lecture was nephritic and nephrotic syndromes. I thought it might help to review them a bit, since they can be maddeningly frustrating if you don’t understand the underlying principle in each one.

Here are the four main characteristics of each:

Nephrotic syndrome

- Massive proteinuria

- Hypoalbuminemia

- Edema

- Hyperlipidemia/hyperlipiduria

Nephritic syndrome:

- Hematuria

- Oliguria

- Azotemia

- Hypertension

How do you make these lists hang together in a way that you can remember?

First, let’s take nephrotic syndrome.

The thing to remember for this one is massive proteinuria. You might do this by remembering that nephrotic and protein both have an “o” in them. The massive proteinuria in these patients leads to hypoalbuminemia (they are peeing out albumin!), which results in edema (the oncotic pressure in the blood goes down, and fluid leaks out of the vasculature into the surrounding tissue).

So right there, you have three of the four features, just by remembering one. The hyperlipidemia/hyperlipiduria occurs because as the liver is trying to make more albumin (to make up for the albumin loss in the urine), it also ends up making more lipids.

As an aside, nephrotic syndrome is often more dangerous than nephritic syndrome, so you might want to think of this syndrome as the “oh sh*t” syndrome (again – nephrotic has an o in it, nephritic does not). Crude, but if it works, who cares?

How about nephritic syndrome?

In nephritic there is some proteinuria and edema, but it’s not nearly as severe as in nephrotic syndrome. The thing with nephritic syndrome is that the lesions causing it all have increased cellularity within the glomeruli, accompanied by a leukocytic infiltrate (hence the suffix “-itic”). The inflammation injures capillary walls, permitting escape of red cells into urine. Hemodynamic changes cause a decreased glomerular filtration rate (manifested clinically as oliguria and azotemia). The hypertension seen in nephritic syndrome is probably a result of fluid retention and increased renin released from ischemic kidneys.

Bottom line

If you really want to pare it down, just remember that nephrotic syndrome is characterized by massive proteinuria (the “o” in nephrotic), and nephritic syndrome is characterized by inflammation (the “-itic” in nephritic). Then at least you’ll have a shot at remembering the other features.

If you want to read more, you might want to take a look at “What causes nephritic and nephrotic syndrome” as a little review of the diseases we talked about in class.

Conjugated vs. unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia

In the Liver/Pancreas/Gallbladder lecture, I talked about the things that cause an elevation in serum bilirubin (hyperbilirubinemia).

I also talked about how it’s useful to know whether the patient has an elevation in conjugated or unconjugated bilirubin (because that helps you narrow down the possible causes).

Here’s a question and explanation to get you thinking about this a bit more.

While examining the gums of a 25 year old patient, a yellowish discoloration of the oral mucosa and sclera is noted. Laboratory tests show a significant increase in unconjugated bilirubin. Which of the following disorders is most likely the cause of this patient’s abnormalities?

A. A stone in the bile duct

B. Carcinoma of the head of the pancreas

C. Pancreatic pseudocyst

D. Sickle cell disease

E. Hepatocellular carcinoma

What’s the correct answer?

Let’s review a little before we get to the question.

Bilirubin is a breakdown product of heme (which, in turn is part of the hemoglobin molecule that is in red blood cells). It is a yellow pigment that is responsible for the yellow color of bruises, and the yellowish discoloration of jaundice.

When old red cells pass through the spleen, macrophages eat them up and break down the heme into unconjugated bilirubin (which is not water soluble). The unconjugated bilirubin is then sent to the liver, which conjugates the bilirubin with glucuronic acid, making it soluble in water. Most of this conjugated bilirubin goes into the bile and out into the small intestine. (An interesting aside: some of the conjugated bilirubin remains in the large intestine and is metabolized into urobilinogen, then sterobilinogen, which gives the feces its brown color! Now you know.)

So: if you have an increase in serum bilirubin, it could be either because you’re making too much bilirubin (usually due to an increase in red cell breakdown) or because you are having a hard time properly removing bilirubin from the system (either your bile ducts are blocked, or there is a liver problem, like cirrhosis, hepatitis, or an inherited problem with bilirubin processing).

The lab reports the total bilirubin, and also the percent that is conjugated (this is usually called the “direct” bilirubin). You can easily figure out, then, how much unconjugated bilirubin you have (it’s just the total bilirubin minus the direct bilirubin).

If you have a lot of bilirubin around and it is mostly unconjugated, that means that it hasn’t been through the liver yet – so either you’ve got a situation where you’ve got a ton of heme being broken down (and it’s exceeding the pace of liver conjugation), or there’s something wrong with the conjugating capacity of the liver (for example, the patient has hepatitis and it’s interfering with the liver’s ability to conjugate bilirubin).

If you have a lot of bilirubin around and it’s mostly conjugated, that means it’s been through the conjugation process in the liver – so there’s something preventing the secretion of bilirubin into the bile (for example, there’s something blocking the bile duct, or the patient has hepatitis and it’s interfering with bilirubin excretion), and the bilirubin is backing up into the blood.

Back to the question. Let’s go through each answer and see what kind of hyperbilirubinemia these disorders would cause.

A. A stone in the bile duct – if big enough, a stone here could block the excretion of bilirubin into the bile. The bilirubin would already be conjugated, so this would be a conjugated bilirubinemia.

B. Carcinoma of the head of pancreas – this could also cause biliary obstruction, similar to A. (An important aside: it’s nice when pancreatic carcinomas announce themselves this way, because it may allow for earlier detection of the tumor. Unfortunately, this is uncommon. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma is usually silent until the tumor is very large and possibly metastatic.)

C. Pancreatic pseudocyst – same idea as A and B.

D. Sickle cell disease – Sickle cell anemia is a type of hemolytic anemia. Hemolytic anemias often cause unconjugated bilirubinemia (when the hemolysis is massive enough, it’s hard for the liver to keep up, and you get a bunch of unconjugated bilirubin spilling into the blood. If there is just a little hemolysis going on, the liver may be able to keep up and conjugate that extra bilirubin, in which case you’d excrete the conjugated bilirubin normally (through the poopy).

E. Hepatocellular carcinoma – this would fall into the category of blocking excretion of bilirubin. The bilirubin would already be conjugated – so this would be a conjugated hyperbilirubinemia.

So: since A, B, C and E produce only conjugated hyperbilirubinemia, the answer is D, sickle cell disease.

Canvas updated! Plus a couple other things.

I posted the scores for quiz 1 and exam 1 on Canvas. You guys did great on Exam 1 – the mean was 97%! Yay!

Just a quick reminder: I am on vacation until the 25th, so for the next three weeks, we won’t have in-person class. I don’t like being away that long – it feels weird not seeing you guys at all – but I will do my best to keep checking in with you and I am always here if you have questions (just drop me an email).

Looking ahead a bit, this week is pretty simple – just a couple lectures (pancreas/liver/gallbladder and renal) for you to watch at your convenience. The following week, we’ll have Quiz 2 and a lecture on skin. We’ll do Quiz 2 the same way we did quiz one (using Google forms, open-book etc.).

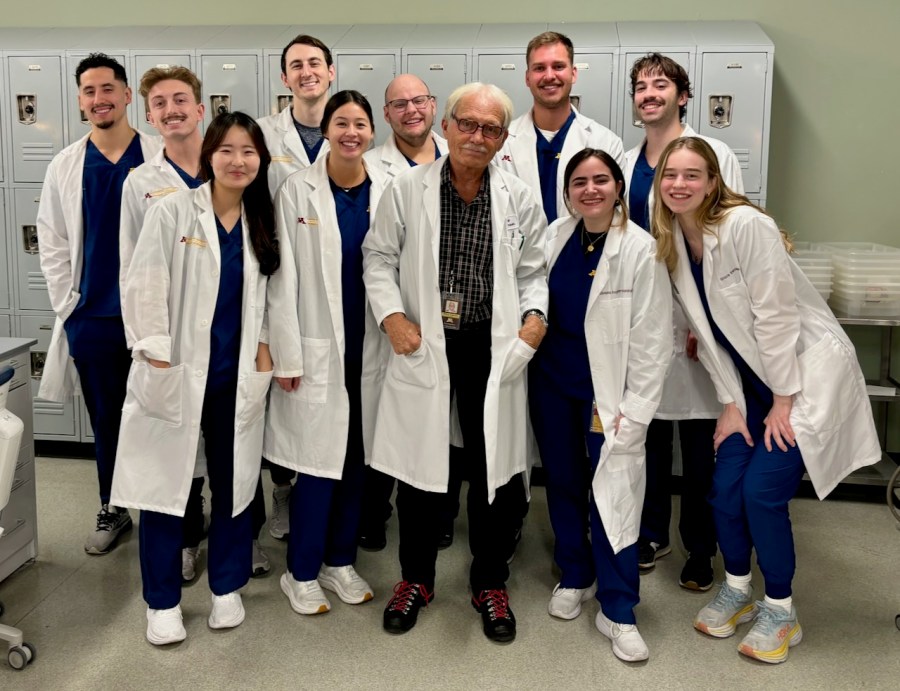

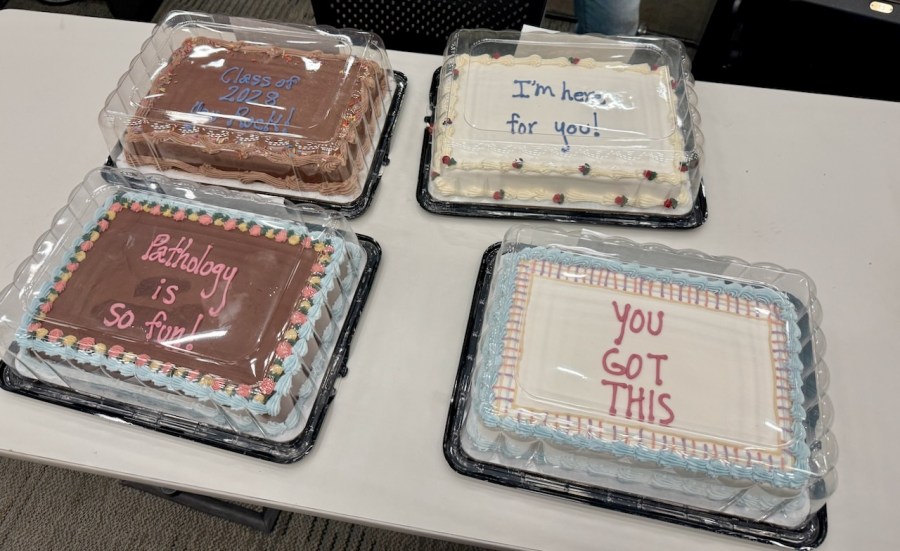

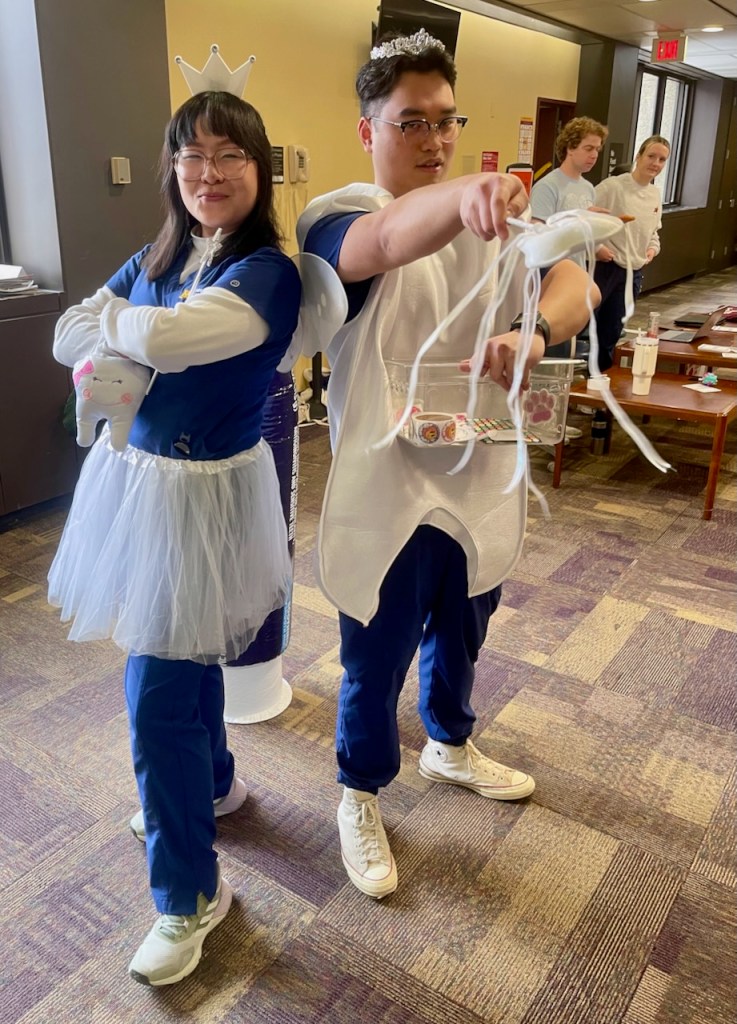

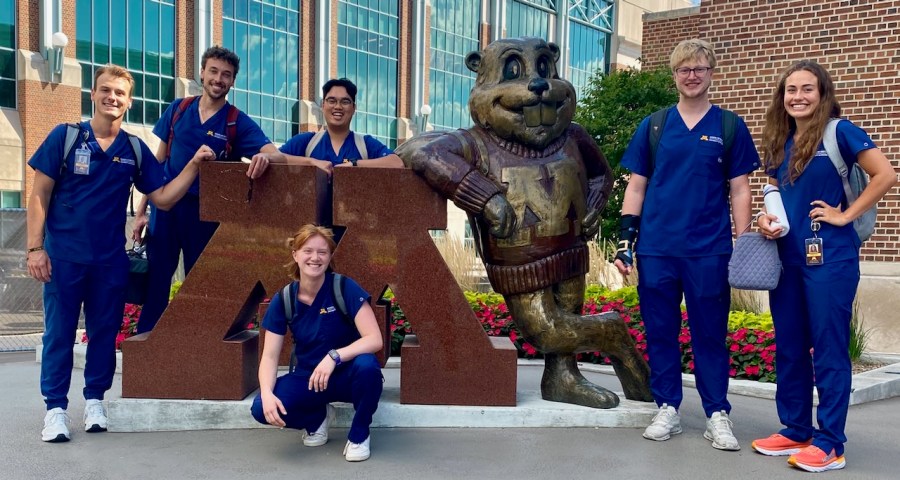

Here are a few photos I took today and yesterday, in case you like seeing other people’s travel photos!